Productivity

1 Tortoise turning into Hare

The fascinating story of Gymnosperm persistence

Fitness of a plant is related to its productivity. In that sense, productivity determines the ranking order of competitive ability of coexisting species.

Wide distribution and diversity not necessarily mean fitness

1.1 Gymnosperms v/s Angiosperms

Angiosperms first appeared in the Cretaceous period and proliferated. As they diversified and multiplied, gymnosperms, once dominant vegetation started receding to high altitude or nutrient poor soils.

Yet the productivity of gymnosperms often equals or exceeds potentially competing angiosperms and they live longer. In fact, they are among the oldest and largest living plants known to man.

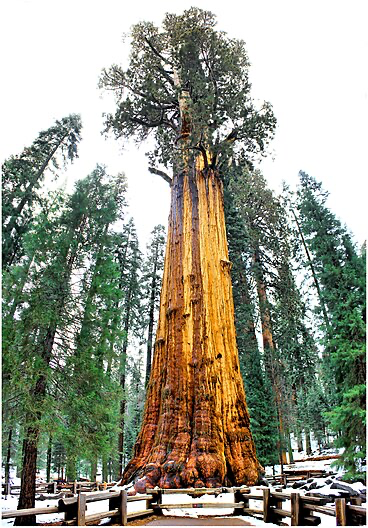

General Sherman in fig 1, a redwood (Gymnosperm) of the California forest is the largest tree in the world and is having an estimated age of 2300-2700 years.

Lindsey Creek tree the largest tree ever lived was also a redwood, felled by a storm in 1905 was twice as big as General Sherman.

Pinus longaeva, another Gymnosperm, is 4855 years old and still counting.

Why are they confined to rigorous environments?

Why do they yield to the new species when their productivity is superior?

The giant sequoias retreated to tougher terrains seeing low weeds interspersed in their under-story for a reason.

1.2 Factors Affecting Plant Productivity

Productivity of a plant is proportional to:

- Net photosynthesis rate

- Total Leaf area index

- Duration and extend of leaf drop

- Allocation of photosynthetate to leaves or non-photosynthetic tissue

Ultimately what matters here is how much you allocate for the growth (Size of Canopy) and how much capital is preserved in that process. If there is seasonal loss of leaves (Capital), ultimate productivity will be low.

1.3 Efficiency v/s Safety

To improve efficiency of water carriage, the Xylem vessels of the angiosperms are larger than gymnosperm tracheids. The rate of flow of water is proportional to the square of the diameter of the vessel.

But this carries a risk. Larger diameter vessels involve greater risk of accidental embolism. To mitigate the risk, trees with larger Xylem vessels are typically deciduous.

Trees with safer narrower tracheid vessels are in general evergreen and grow in water-stressed areas.

1.4 Deciduous v/s Evergreen

As we saw previously in Section 1.3 , shedding leaves periodically is an ingenious way of getting rid of inefficiently embolized conductive systems before the flush of new leaves. They prefer less water-stressed areas and their prolific growth presupposes unlimited abundance of factors of production.

More-over, deciduous nature reduce the opportunity to create a bigger Canopy

1.5 Problem of Prolific Growth

Rapid growth and proliferation in the younger stage attract THIRD PARTY players in the form of Fire, Fungus and Herbivorous before defence mechanisms are developed.

With these points in mind, let’s explore the key differences between Gymnosperms and Angiosperms

1.6 Differences Between Gymnosperms and Angiosperms

Gymnosperms have:

- Long reproductive cycles

- Linear, needle-shaped leaves without venation

- Smaller Tracheids for water transport, no specialized larger Xylem vessels in the stem

- Young gymnosperms take longer to reach maximal leaf area

- Have less foliage and less carbon income for growth allocation and anti-herbivore defence in the early growth period

In contrast, Angiosperms are prolific in reproduction and rapid colonization.

They have:

- Shorter and prolific reproductive cycle

- Complex leaves with efficient venation

- Larger Xylem vessels in the stem for efficient transportation of water

- Young angiosperms take less time to reach maximal leaf area

- Have more foliage and more carbon income for growth allocation and anti-herbivore defence in the early growth period

1.7 What does that mean?

Because of limitations of their transport system, gymnosperms have a lower rate of maximum dry matter production than angiosperms under unlimited growing conditions.

In contrast, equipped with larger vessels and heavily vascularized leaves, angiosperms grow much faster but only where there is no shortage of water or necessary nutrients for production of new leaves.

Gymnosperm seedlings under the shade of rapidly growing angiosperms are rapidly eliminated by surface fire and grazing herbivorous.

However, seedling in open sunlight rapidly gain resistance to surface fire and tend to benefit from third party destruction of angiosperms.

Majority of gymnosperms regenerate in large openings created by such disturbances as fire and wind-storms.

If productivity is relevant to inter-specific competition, one may tend to consider Gymnosperms as classic example for poor competitors as seedlings and juveniles but superior competitors as adults.

Poor early performance can be due to:

- Prolonging the juvenile phase by suppression

- Prolonged exposure to biotic agents

- Angiosperm induced radical change in disturbance cycle e.g: fire

- Normal disturbance cycle preventing gymnosperm maturation

But, importantly, in all four cases, angiosperm competitors are not directly responsible for the demise of conifers.

They act through a THIRD PARTY e.g: Fire, fungus and herbivores

Forests under human care carries another risk. Human interventionalism prevent small surface fires in the forest. This will blow-up the system ultimately leading only to a huge bust, creating uncontrollable deep fires, destroying everything in the process.

A gymnosperm seedling growing under a dense patch of angiosperm herbs can survive and slowly overtake them unless some unprecedented environmental factors intervene, such as deep fire. The slow-growing tortoise gradually changes into a hare, beating angiosperms in their own game.

C: Conifer, A: Angiosperm, Arrow going down: Low growth phase of C

Moreover, gymnosperms are least threatened by angiosperms in climates with short growing seasons or on nutrient-poor soils where growth is slow to close the regeneration gap.

If water is seasonally deficient, or the nutrients limiting, then gymnosperms with narrow tracheids and stress tolerant weakly vascularized evergreen leaves thrive.

If there is abundant water, light, and nutrients and long growing seasons gymnosperms can easily be out-competed by angiosperms.

2 Conclusion

Giant sequoias are destined to be giants. They are destined to live longer, taller and broader. Living with short-lived, smaller but prolific younger cousins create great risk to their destiny. They opportunistically retreat to areas where their cousins cannot come. There they grow to become the largest and live for thousands of years.

Then a great surface fire comes to attack the densely populated nutritious, moistureus land of the angiosperms and they vanish.

The heat-tolerant gymnosperm seedlings grab the area.