What is Interval Training?

Interval training refers to repeated bouts of relatively intense exercise interspersed with recovery periods of lighter exercise or rest. This method has been used for over a century by high-level athletes to enhance performance in endurance-based sports such as middle- and long-distance running.

More recently, interval training has also gained recognition for its health benefits, including its role in rehabilitation and improving fitness in inactive or deconditioned individuals(Coates et al. 2023).

HIIT

Nowadays, High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) is ranked as the most popular fitness trend globally. Its popularity stems from its ability to:

Serve as an effective alternative to traditional endurance training.

Yield higher levels of endurance performance.

Reduce time commitment and improve exercise adherence.

Proven Benefits of HIIT

HIIT has demonstrated significant benefits in various populations, including:

Athletes: Improved VO2max and endurance performance.

Healthy Individuals: Enhanced fitness levels.

Overweight/Obese Individuals: Better metabolic health.

Cardiac Patients: Improved cardiovascular function.

HIIT Protocols

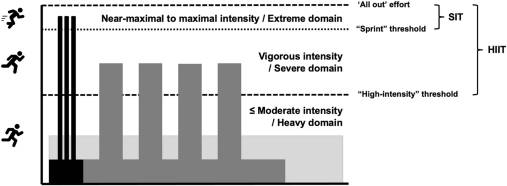

HIIT can be classified into various protocols based on work intensity, bout duration, session volume, and intervention duration(Wen et al. 2019):

| Protocol Type | Details |

|---|---|

| Long-Interval HIIT (LI-HIIT) | Work bouts lasting 2–4 minutes at sub-maximal intensity. |

| Short-Interval HIIT (SI-HIIT) | Work bouts lasting <45 seconds at sub-maximal intensity. |

| Sprint-Interval Training (SIT) | Work bouts lasting 20–30 seconds at near-maximal to maximal intensity. |

| Repeated-Sprint Training (RST) | Work bouts lasting ≤10 seconds at near-maximal to maximal intensity. |

Volume and Duration Variations

HIIT protocols can also differ based on session volume and intervention duration:

Session Volume

- High-Volume HIIT (HV-HIIT): Sessions with 16 minutes or more of work.

- Low-Volume HIIT (LV-HIIT): Sessions with 4 minutes of work.

Intervention Duration

- Long-Term HIIT (LT-HIIT): Training programs lasting ≥12 weeks.

- Short-Term HIIT (ST-HIIT): Training programs lasting ≤4 weeks.

Even short work interval (≤30 s), low-volume (≤5 min) and short- term (≤4 weeks) HIIT could elicit clear beneficial effects on VO2max when compared to no exercise(Wen et al. 2019).

Low-Volume Sprint Interval Training (SIT)

Low-volume Sprint Interval Training (SIT), which can be cosidered a subset of HIIT,involves:

- Very High-Intensity Intervals: Work intervals lasting approximately 30 seconds.

- Short Duration: Each bout of activity is brief but intense.

- Long Recovery Periods: Rest intervals lasting around 4 minutes between each bout.

Benefits of SIT

Studies suggest that SIT can produce improvements in:

Aerobic Power: Comparable to traditional endurance training.

Metabolic Function: Enhances energy efficiency and metabolic health.

SIT provides an efficient alternative to traditional endurance training while maintaining similar physiological benefits. SIT has garnered considerable attention as a time-efficient and alternative method for enhancing aerobic performance and metabolic function(Sloth et al. 2013).

Definition

Duration of Bouts: 10–30 seconds

Intensity: Maximal effort, “all-out”

Volume: ≤12 repetitions

Recovery: ≥5 times the duration of each work bout

Sprint Interval Training (SIT) involves specific criteria to optimize its effectiveness. Bout durations are set between 10 and 30 seconds. Durations shorter than 10 seconds are excluded as they rely predominantly on anaerobic metabolism and have shown no significant impact on mitochondrial enzymes(M.-T. Linossier et al. 1993);(M.-T. Linossier et al. 1997);(BOGDANIS et al. 1998);(Dawson et al. 1998). The upper limit of 30 seconds is based on evidence that longer bouts significantly increase aerobic contribution to ATP turnover(Withers et al. 1991) and lead to a marked reduction in intensity, which disqualifies them from being classified as low-volume SIT. Intensity is characterized as “all-out” or near-maximal effort, adhering to the general conception of a sprint(Ross and Leveritt 2001). Volume and recovery protocols are designed to maintain a low total training volume while ensuring that high power output can be sustained across all sprints within a session.