Sequence of return risk

First, we can summarise what we have learned from the previous post on risks: Market risk is not the only risk in market.

We invest into the future to meet future needs and wants. Historically, capital equity markets have outperformed other asset classes, so some of us tend to use equity as a vehicle to accumulate wealth. Market risk refers to the uncertainty in the average return we will realise by doing so. Beyond this, hidden risks—namely volatility risk, , inaction risk, and sequence of return risk—can affect our final Total Portfolio Value (TPV). We saw that the sequence in which we receive varying returns can have a profound impact on TPV, particularly when we are adding or, more importantly, withdrawing money from the portfolio. This risk vanishes if there are no additions or withdrawals, as CAGR is calculated by multiplying returns at different intervals of time.

TPV = P * (1+r1 )* (1+r2 )*… * (1+rn )

In a series of multiplications, the order does not matter. This holds true if we withdraw or add a fixed percentage of the portfolio instead of a fixed amount of money, as in a SIP or SWP.

Assume w is the fixed percentage we withdraw or add every period (say, yearly). The new returns will be:

R1 = r1 ± w

R2 = r2 ± w

Rn = rn ± w

The new formula becomes:

TPV = P * (1+R1)* (1+R2)* … * (1+Rn)

Sequence of return risk will not affect you if a fixed percentage of the portfolio is withdrawn instead of a fixed amount of money.

However, by removing sequence of return risk from the portfolio, we introduce another problem: our withdrawal rate is fixed. This means the amount of money you may withdraw each year is uncertain; it depends on the TPV for that particular year, which is in turn dependent on the portfolio’s return for that year. A drawdown of 52% would reduce your withdrawal amount by 52%. This gives us another compelling reason to somehow trim downward volatility risk.

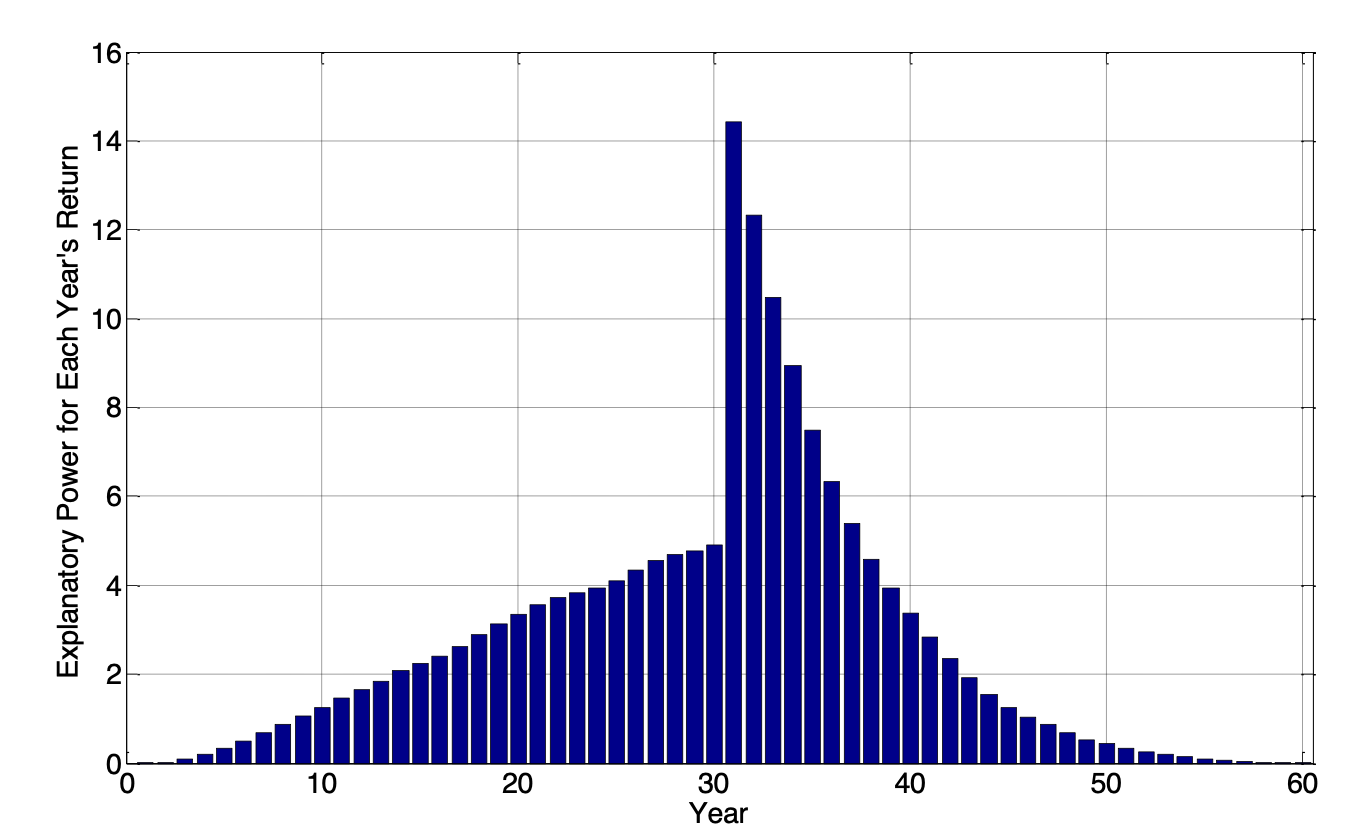

Once again, sequence of return risk affects you during both the accumulation phase and the distribution phase of wealth, if you add or withdraw a fixed amount of money. Below is an important graph depicting the effect of each year’s return on TPV (Pfau 2013). We are particularly vulnerable to what happens at the beginning of the distribution phase and in the 4-5 years following the start date of distribution. In fact, the first year’s return has a staggering 14% effect, which gradually reduces to around 7% by the 5th year.